Feebate/Rebate or Fiscal Failure?

JAKARTA (August 12, 2025). Fiscal policy for motor vehicles in Indonesia is at a crossroads. For more than a decade, a series of incentives, particularly tax exemptions for the Low Cost Green Car (LCGC) category, have been implemented through Government Regulation No. 41/2013 with the aim of encouraging the adoption of low-emission vehicles. However, instead of accelerating the adoption of energy-efficient vehicles through the implementation of Low Carbon Emission Vehicles (LCEVs), which was the primary mission and the reason for the issuance of the PP, the existing policy has instead created a paradox: a significant burden on the state budget without a proportional impact on reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The implementation of PP No. 41/2013 was sabotaged solely for the sake of boosting penetration of the national automotive market, which was sluggish at the time due to declining purchasing power, by pragmatically pursuing affordable vehicles. In addition to introducing vehicles with downsizing technology, which is highly dangerous because it reduces safety levels in order to achieve fuel efficiency and affordable prices, this policy also neglected the primary mission of implementing LCEVs.

Only ten years later, amidst the global trend toward adopting low-carbon vehicles, in accordance with the spirit of Presidential Decree No. 55/2019, along with various related regulations that seek to realize the mandate of Law No. 16/2016 concerning the Ratification of the Paris Agreement, did the government implement its support for LCEVs by providing fiscal incentives for Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs). In April 2023, the government began providing incentives in the form of tax rebates, allowing BEV buyers to pay only 53% of the 83% tax they would otherwise pay. In practice, buyers of electric motorcycles and electric cars received price reductions of Rp 7 million and Rp 80 million, respectively. Against the backdrop of concerns about the climate crisis at that time, along with predictions of a worsening climate crisis, particularly by 2100, with catastrophic impacts, the Paris Agreement was agreed upon as a global agreement to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and prevent a worsening climate crisis. BEV adoption is indeed a strong recommendation of the Paris Agreement.

The issue remains unresolved. ICE technology, which produces fuel-guzzling, carbon-emitting vehicles, is attempting to influence the fiscal incentive policy for BEVs. Government policy has been shaken and BEV fiscal incentives have begun to be relaxed, citing fiscal space constraints. Amid this stagnation, a radical alternative has emerged: a carbon emission-based fiscal scheme (feebate/rebate) implemented on a revenue-neutral basis in the state budget (budget neutrality). The analysis presented at this FGD organized by the Ministry of Environment (Jakarta, August 12, 2025) examines the structural failures of the current incentive policy and evaluates the potential of a carbon excise tax system and low-carbon incentives as a more effective, equitable, and sustainable solution for the Indonesian automotive market.

Questionable Effectiveness

Since 2013, the government's primary instrument has been the Luxury Goods Sales Tax (PPnBM) exemption for low-carbon emission vehicles. However, as mentioned above, its implementation is considered fraught with distortions in the interests of the automotive industry, resulting in it being applied only to LCGCs.

"Imagine, from 2013 to 2023, approximately 10 years, only LCGCs received incentives," said Ahmad Safrudin, Executive Director of the Leaded Gasoline Elimination Committee (KPBB). He highlighted the discriminatory nature of the policy. "There are vehicles that are actually low-carbon but don't receive incentives. For example, LCEVs (Low Carbon Emission Vehicles). Some variants are already categorized as LCEVs but don't receive incentives because they aren't categorized as LCGCs."

Reliance on the state budget is also a fatal weakness. Every incentive means a reduction in state revenue. "If the government continues to provide incentives, it will certainly become a burden because government revenue or tax revenue will be significantly reduced," Safrudin continued. This dependence makes the policy uncertain and vulnerable to political discontinuation, as is currently happening, triggering uncertainty in the electric vehicle industry.

The Health Costs of Air Pollution

The focus on incentives without disincentives for high-emission vehicles has overlooked the external costs borne by society. Air pollution from the transportation sector has real health and economic impacts.

"We need to realize here that air pollution is a local issue and our own responsibility," emphasized Dr. R. Dierjana, an academic from Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB). She underscored the potential crisis in the health insurance system. "The health impacts of air pollution pose a threat to the BPJS (Social Security Agency for Health)."

KPBB data supports this argument. "Our 2016 study showed that Jakarta residents had to pay Rp 51.2 trillion in medical costs, both personally and through BPJS," said Ahmad Safrudin. This cost represents a massive economic burden arising from policies that fail to effectively control pollution sources.

Carbon-Based Fiscal Scheme (Feebate/Rebate Fiscal Scheme)

As a solution to the systemic fiscal weakness of low-carbon vehicles, the KPBB proposes a feebate/rebate fiscal policy scheme integrated with carbon emission levels (gr CO2/km).

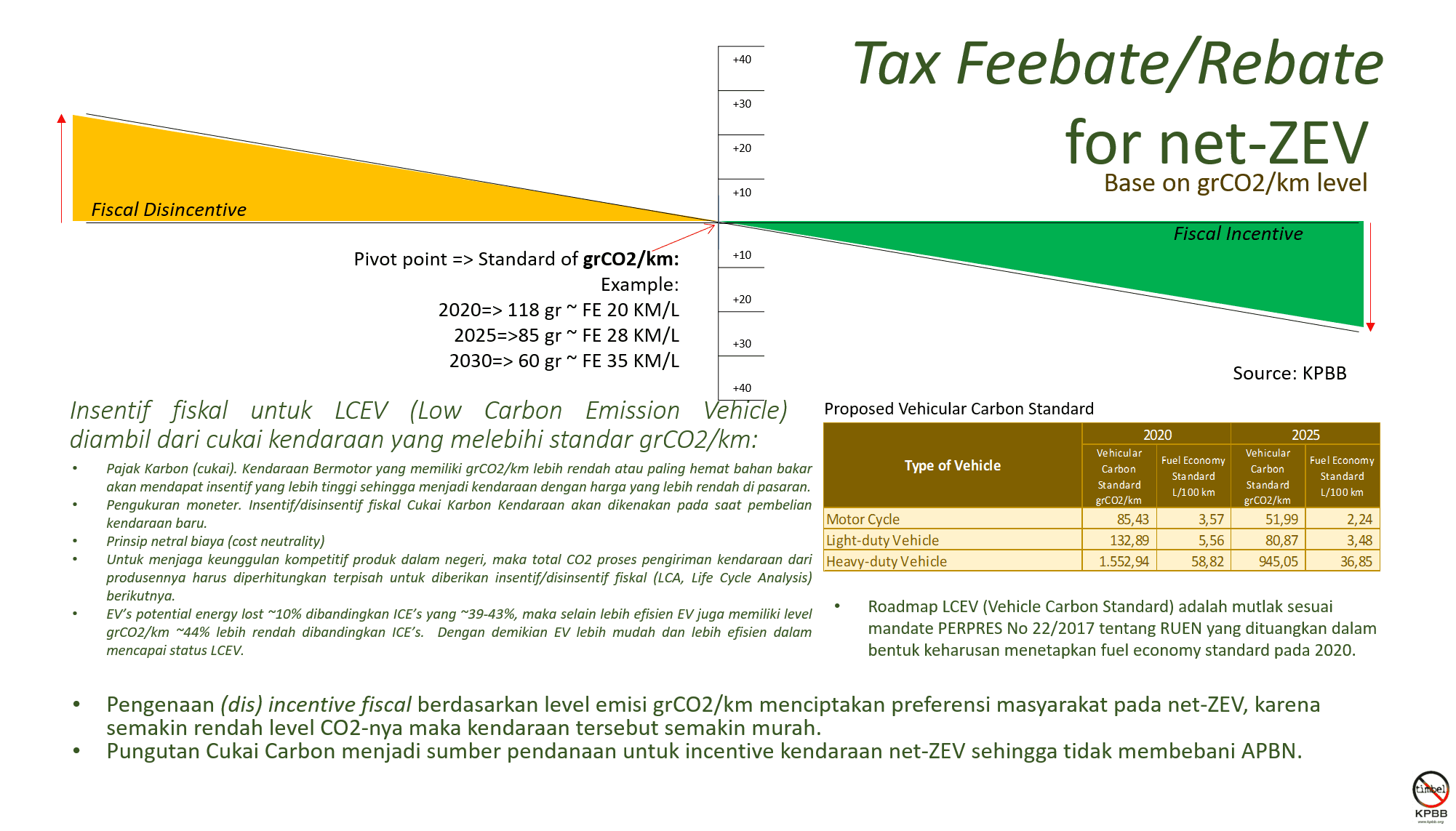

The working mechanism begins with Standard Setting, where the Government sets a carbon emission threshold for each vehicle category (gr CO2/km). This standard is a pivot point established in accordance with developments in vehicle carbon emission reduction technology. Next, a feebate (fine) is imposed on vehicles whose emissions exceed the standard in the form of a carbon excise tax proportional to the carbon level. "The higher the carbon... the higher the excise tax that must be paid. So, this excise is imposed on each gram of carbon exceeding the standard and multiplied by a certain value—the price of the carbon reduction technology—and the total must be paid by the vehicle buyer," explained Safrudin.

In parallel, the government also provides a rebate option (incentive in the form of a fiscal discount). Vehicles with emissions below the standard are eligible for incentives. "If we buy a vehicle with a carbon level far below the standard... we will receive an incentive," he added. The value of this incentive is based on the vehicle's ability to reduce carbon emissions below the standard or threshold. Every grCO2/km below the set standard will be taken into account as performance to obtain tax rebate incentives, so that vehicles with low carbon levels will have a cheaper selling price.

In this scheme, vehicle buyers have 2 options, continue to buy high carbon vehicles or vice versa choose low carbon vehicles. Each has consequences, if you want cheap then you will buy a low carbon vehicle, and vice versa.

The main principle is budget neutrality. Funds collected from fines (feebates) are used entirely to fund incentives (rebates), so they do not burden the APBN. And when there are signs that the fiscal space in this scheme is starting to become deficit, meaning when the situation has reached a situation where the government must cover the shortfall in carbon excise revenue to provide incentives for low-carbon vehicles, then that is the right time to tighten carbon standards.

Price Shift Simulation

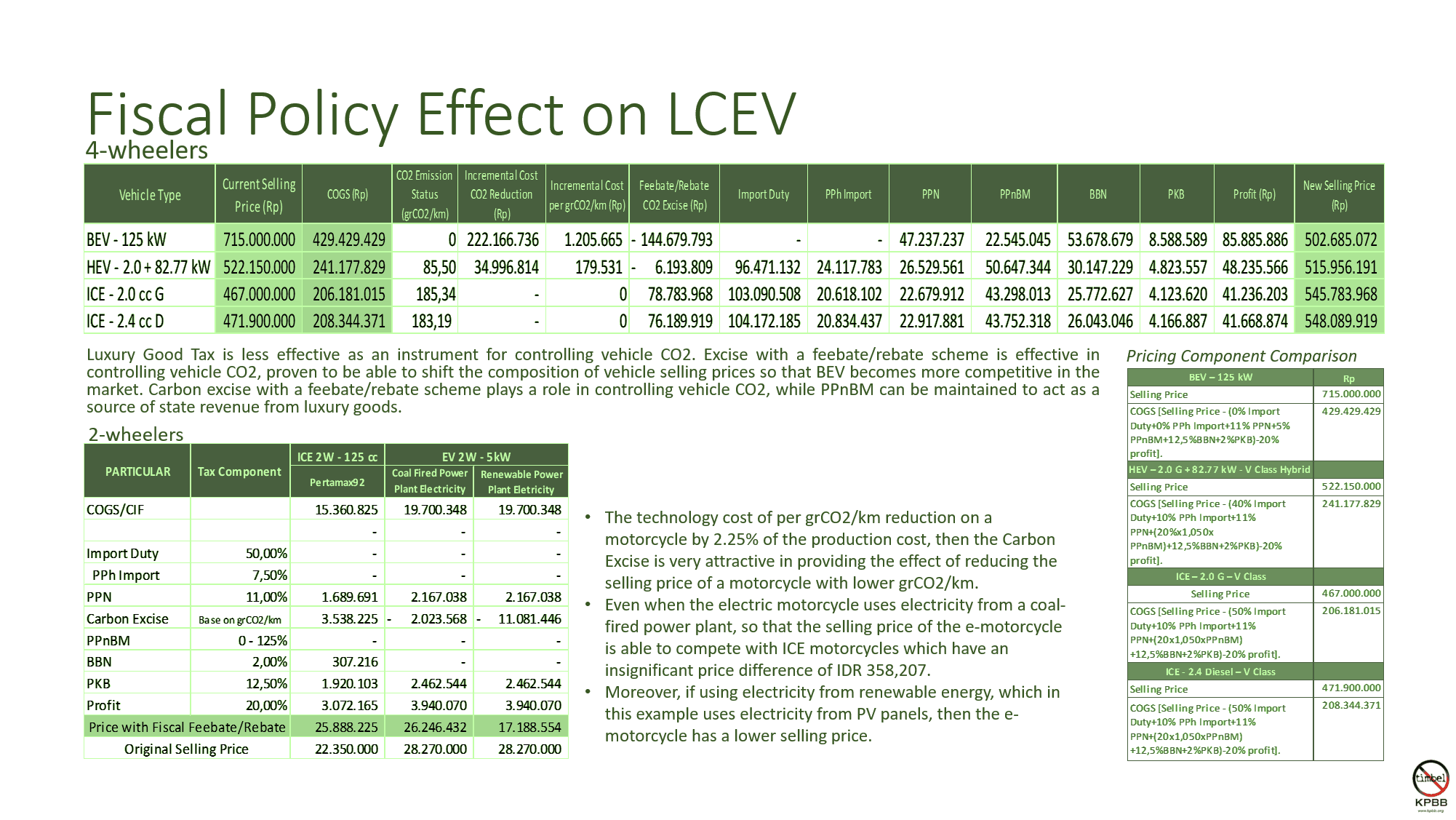

The KPBB simulation demonstrates the potential for dramatic price shifts, which could fundamentally alter consumer behavior and preferences for vehicles. The simulation of passenger vehicles involving a 125 kW BEV, a 2.0+ kW HEV, a 2000 cc gasoline engine, and a 2400 cc diesel engine demonstrated the potential for shifting vehicle pricing. Before the fiscal scheme was implemented, BEVs were the most expensive, at IDR 715 million per unit, followed by HEVs, diesel engines, and gasoline engines, at IDR 522 million, IDR 471 million, and IDR 467 million, respectively. After the implementation of the carbon-based feebate/rebate fiscal scheme, BEVs became the most affordable vehicles, followed by HEVs, gasoline engines, and diesel engines. According to the polluters pay principle, the highest-carbon vehicles become the most expensive. This also applies to motorcycles. See the table for 2-Wheelers.

The advantages of implementing a feebate/rebate fiscal scheme include: the government can provide incentives for low-carbon vehicles without being burdened by reduced fiscal space (decreased state revenues); existing vehicle tax policies (import duties, import income tax, VAT, biofuel, and vehicle sales tax) remain in place to generate state revenue; there is no discrimination based on technology use; there is potential for a competitive advantage program for domestic low-carbon vehicle production; low-carbon vehicles, such as electric vehicles, become more price-competitive; there is the creation of a market mechanism that encourages the adoption of clean technology; and a shift in market preference toward low-carbon vehicles, thus effectively achieving the 2030 ENDC and the 2045 NZE targets in the automotive sector.

Conclusion

Indonesia is currently at a crucial crossroads. Analysis shows that the conventional fiscal incentive approach over the past decade has not only failed to accelerate the energy transition but has also burdened state finances and distorted the market. On the other hand, a market-based alternative through a feebate/rebate fiscal policy scheme offers a conceptually fairer, more effective, and more sustainable solution because it does not rely on the state budget.

However, the path to implementation faces two latent challenges. First, there is the potential for resistance from industry players who persist with high-emission technologies. Second, and most crucially, there is the fragmentation of inter-ministerial policies, which have so far proceeded without coherent synchronization. As industry representatives highlighted, "there is currently no one to conduct this orchestra."

Ultimately, this transformation is not merely a technical issue, but a test of political will. A clear roadmap, from establishing a legal framework to pilot projects, is a necessary step. Successfully shifting from an ineffective subsidy model to a market-based mechanism will determine whether Indonesia can break through stagnation, achieve its 2045 Net Zero Emissions target, and reduce the burden of public health costs reaching tens of trillions of rupiah.

As emphasized in the FGD above, the momentum is now: "Motor Vehicle Carbon Standards must be established immediately. Carbon standards serve as a reference for controlling motor vehicle carbon levels through fiscal incentive/disincentive instruments." The question is no longer whether these changes are necessary, but how quickly policymakers can orchestrate these transformative steps towards NZE 2045. oo0oo (SK/AS).